Google Reader is one of top five most-used websites. I literally always have a reader tab open in Chrome. So when I heard that Reader is shutting down on July 1st, I was like

But after a while I was like

And now I’m like…

…because I’ve concluded that I’m glad Google is shutting down Reader.

Why, dear reader? Because of Game Theory (obviously)! By shutting down Reader, Google is breaking a bad Nash Equilibrium which has been hobbling the progress of web content distribution.

Whoa, what does that mean?

Well, “Game Theory” is simply a mathematical examination of the ideal strategy for playing games. Unsurprisingly it often applies to business and other competitive situations.

Let’s consider the canonical example Game Theorists love to use: “the prisoner’s dilema”. In this scenario, the cookie monster and his brother (Charleston) have both been arrested for, you guessed it, home invasion and murder. The cops put them into two separate cells and start questioning them.

“Now look, cookie monster, I’m not going to lie. Our evidence here is weak. If neither of you confess then we’re going to have to take this to trial, and you might both get off. But I’ll offer you a deal. If you testify against Charleston, we’ll give you immunity and five cookies. Unless, of course, he testifies against you in which case you’ll be learning to count to twenty to life.”

The police say the same thing to Charleston. So what is the cookie monster to do? He has two choices: “cooperate” with Charleston and go to trial, or “defect” and rat him out in exchange for sweet cookies (or long jail time if Charleston also defects.) Charleston has the same choices.

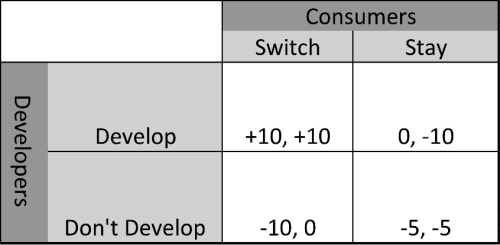

To figure out what both should do, we can make a simple matrix:

Cookie Monster is Player A, Charleston is Player B, and the numbers in each square are the number of cookies each gets in each situation, respectively. (No, the numbers don’t match up; I’m borrowing the diagram.)

Obviously, both monsters are better off if they both cooperate. But that won’t happen, at least not assuming that both care exclusively about maximizing their individual cookie intake.

Why not? Remember that our monsters are in separate rooms and cannot coordinate. Also, notice that each monster is individually best off in the situation where the other monster cooperates but he defects. So if either monster suspects that the other one will be generous and cooperate, his individual narrowly rational best option is to defect. And so he will.

Now the phrase “Game Theory” might quite appropriately make you think of the movie “A Beautiful Mind”. And if you saw that movie, you might think that Russell Crowe (a.k.a. “John Nash”) got academically famous for figuring out how to use game theory to pick up women in bars. But actually he got famous for inventing the concept of a “Nash Equilibrium”.

To over-simplify, a Nash Equilibrium is a set of player choices in a game (e.g. “Cookie monster -> defect”, Charleston -> defect" in the prisoner’s dilema) that will produce an outcome which neither player can improve by changing his choice unilaterally.

Take another look at the prisoner’s dilema diagram. The bottom right square is a Nash Equilibrium because, even though it is the worst outcome it’s the best that either player can do for himself. If Charleston thinks cookie monster is going to defect, he makes himself even worse off by cooperating. Same for cookie monster.

So in games where a Nash Equilibrium exists, we can generally expect that it will come to pass.[1][2]

So how does this all apply to Google Reader? Well, the existence of Google Reader has created and trapped us in a bad Nash Equilibrium. In this case, Google isn’t actually a player. Google is literally and figuratively out of the game – they haven’t cared about Google Reader in years and have let it wither on the vine.[3]

Instead, the players are consumers of RSS content and developers of alternative RSS readers.

The developers have two choices,

- develop a new, better reader

- do nothing, and let people continue to use Google

And the consumers have two choices:

- switch to an alternative

- keep using Google reader

We end up with something that looks an awful lot like the prisoner’s dilema, but with a few key differences.

It’s still the case that everyone is better off if consumers and developers cooperate on moving to a new reader. But it’s no longer the case that one side gains because the other loses. This is actually a game with two Nash Equilibria (develop, switch) and (don’t develop, don’t switch.) And instead of being played once in a jailhouse, this decision process is repeated every day.

Games with multiple equilibria (which I am of course oversimplifying here) introduce a fascinating question: “given that there’s a better state which both sides can agree is better for them individually how can move to that better world?” Remember that in a Nash Equilibrium, neither side can improve her outcome by changing her move unilaterally. But if the sides can coordinate then it’s as simple as agreeing to change their decisions at the same time.

But in the real world of RSS readers, developers can’t practically coordinate en masse with consumers. Each has to speculate in isolation about what the other will do. So we end up in a world where fear reigns and consumers don’t investigate alternative RSS readers because they fear that the other options are even more primitive. And although developers could make something much better, they don’t want to risk investing the development time and having no one show up (since GR is “good enough” for most people.)

And so for years we’ve been muddling along in the bad Nash Equilibrium of continuing to use GR and letting RSS become “uncool” relative to social sharing (despite being, IMHO, about 10x more useful.)

But when Google shuts down Reader, the whole game changes. Suddenly the bad Nash Equilibrium square is out of play. That means that coordination between developers and consumers is no longer necessary because “staying put” is no longer an option.

The immediate aftermath might be painful, but I predict that we’ll all end up with a much better system.

Also, note that this dynamic is hardly exclusive to GR. It’s all over the tech world: some company develops a product which gets popular; they lose interest and stop improving. But they keep the product alive, and the network effects and switching costs keep people using it even though much better mechanisms are theoretically possible. The two worst offenders I can think of are:

- Craigslist

- Javascript

Both are terrible but both are extremely widely used. And so we’re stuck in a bad Nash Equilibrium where everyone suffers because it’s too hard to get people to sell their broken furniture on a new website when they can just use Craigslist and it’s too risky for Mozilla to implement Python in the browser when developers might just keep kludging JS.

If Craigslist would just take a lesson from Google and shut down completely, it would be one of the best days ever in tech.

Can you think of better examples of “okay” products that could help the world by just disappearing? Please comment and let me know!

[1] Game theory is complicated, and there are a lot of exceptions depending on circumstances. But simplification usually gets us close enough.

[2] The prisoner’s dilema is one of the saddest abstract constructs I know. In a painful nutshell, it explains why “we can’t all just get along.”

[3] Not because they don’t care per se, but because it’s just not impactful enough relative to their other lines of business